Cast iron seasoning is a layer of polymerized oil that creates a natural nonstick surface. The best way to build it: cook with your pan regularly using fat or oil. Pre-seasoned pans are ready to use but not fully nonstick yet—some sticking is normal early on. Build seasoning by cooking with generous fat, keeping heat low to medium, and avoiding acidic ingredients for the first 15-20 sessions. Oven seasoning is optional; if you do it, use grapeseed or sunflower oil (avoid flaxseed), start at 200°F, increase to 400°F for one hour, and wipe away excess oil until the pan has a dry, matte finish.

Do I Need to Season a Pre-Seasoned Skillet?

These days, most cast iron manufacturers pre-season skillets, us included. You can cook with these pans right out of the box, but they won’t actually be totally non-stick. The Field Skillet, which comes coated with three seasoned layers of grapeseed oil, is actually less pre-seasoned than other producers, because we focus on baking seasoning into the pan, not on top of it. But we’ve found this approach develops better subsequent layers of seasoning over time, compared to other pans that try and speed up the process by covering up the iron with a more cosmetic top coat.

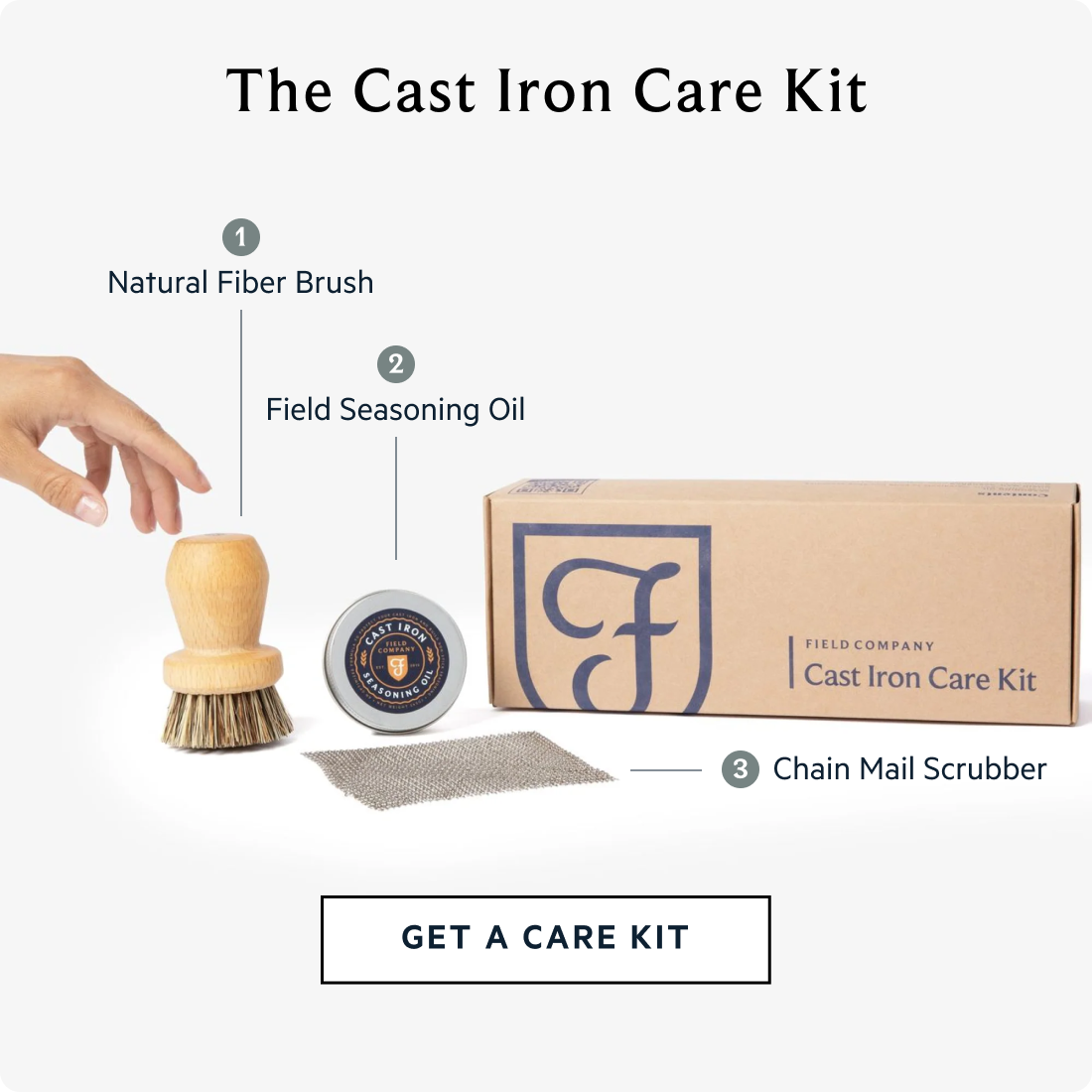

You don’t have to oven-season a Field Skillet, or any pre-seasoned cast iron pan; whether you want to is up to you. Early in the lifetime of your pan, some proteins like bacon and eggs may stick a bit. This is fine, and all part of the gradual seasoning process — and our Seasoning Oil is engineered to help. The most important thing to do is cook with it often, and to follow our guidelines below over the first 15 to 20 sessions with your pan.

What is Seasoning?

Seasoning is the black patina that builds up on your cast iron skillet with regular use, a non-stick surface that’s slick enough for eggs to skate across the pan, but tough enough to withstand the blazing heat needed to properly sear a steak. It’s the at-home work you do to turn a cast iron pan into an heirloom, and it’s as important for your cooking as the iron your pan is made from.

There’s a lot of advice on the internet about seasoning and cast iron care, and a lot of misinformation as well, so we want to set the record straight on what you really need to know to season a cast iron skillet correctly. We’ve spent years obsessing over how to make the best cast iron pan, which means we’ve devoted hundreds of hours to researching and comparing different ways to season it. That’s included testing a wide range of oils, heat ranges, and techniques while consulting chemists, machinists, and cast iron lovers around the country.

When subjected to high heat, long chains of fat molecules break down into short-chain polymers that bond with naturally produced carbon and bare iron, forming a kind of glaze. This is seasoning, and it has smooth, non-stick properties similar to Teflon. It also forms a natural barrier between the air and the naked iron in your pan, acting as the first line of defense against rust.